The Museum of Jewish Heritage in Lower Manhattan, like other institutions that memorialize the Holocaust, has long relied on survivors to provide firsthand accounts of the cruelties imposed by the Nazis and the various paths people took to endure.

But with the ranks of survivors thinning — almost all are in their 80s or 90s — the museum has been working to find the most effective ways to convey to future generations how easily a civilized society can descend into almost incomprehensible barbarism and systematic mass slaughter.

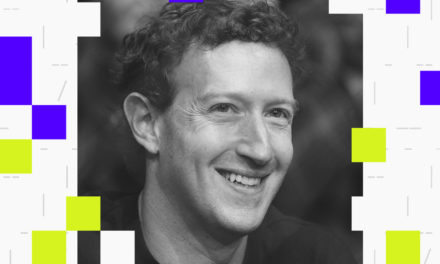

“What I care about is what your grandchildren’s grandchildren will know,” said Jack Kliger, the museum’s president and chief executive, a son of survivors.

In planning for what Kliger calls “a post-survivor world,” the museum could have simply offered taped videos of individuals recounting their painful experiences. But museum officials worried that such an approach risked putting forth a fragmented and misleading sense of what happened; that someone viewing, say, the testimony of a prisoner of a concentration camp might think that all Holocaust survivors spent World War II in concentration camps.